Robert Neimeyer is a professor of psychology and active clinician at the University of Memphis. He has authored a prolific amount of scholarly work in psychology and grief studies. Neimeyer has also held many titles, such as president of the Association for Death Education and Counseling (ADEC), and has received honors such as the lifetime achievement award by both ADEC and the International Network on Personal Meaning.

Q. The first volume of Techniques of Grief Therapy (TGT) focused on Creative Practices for Counseling the Bereaved. What inspired you to devote this volume to Assessment and Intervention?

A. Good question. Perhaps the simplest response is that in the course of my frequent travels to offer professional training workshops, I kept meeting master therapists whose work stirred my curiosity, respect, and sometimes awe. And so, as with the original volume of Techniques of Grief Therapy, I was eager to compile a generous selection of several dozen techniques distilled from their work, and offer them to a broader readership of clinicians like myself who could benefit from the inspiration.

At another level I wanted to reflect the rapid growth in the sophistication of conceptual models, intervention programs, and specific methods addressing vexing problems for bereaved people, problems like ambivalence, guilt, and traumatic imagery, or the challenges of reconstructing a sense of self or reorganizing their attachment bonds to the deceased as well as to the living.

Finally, there has been a great leap forward in the development and validation of very usable clinical measures for evaluating strengths and vulnerabilities of mourners contending with challenges to their world of meaning, their sense of spiritual security, their social support and their grief-related symptomatology.

By including a dozen brief chapters devoted to these scales along with scoring keys, I wanted to encourage their use by clinicians and bereavement care services seeking to pinpoint a client’s needs and document the effectiveness of treatment. I also imagined the inclusion of these same scales would increase their use by clinical scientists interested in evaluating scientifically the outcomes of grief therapy.

Q. Your professional focus is to help people find meaning during loss and transition. What topics and interventions were most important to you to include in this book? What was the process you used to select contributors and techniques?

A. Okay, I confess: I’m a meaning junkie! By that I mean that I view human beings as inveterate meaning makers, seeking sense and significance in the course of living–most particularly when the self narratives we think we are living are shaken or sundered by profound loss and deeply unwelcome change. And I am sure that many of the chapters I wrote or recruited reflect this orientation, as in my opening chapter with Joanne Cacciatore on an adult developmental theory of grief, several of the assessment chapters, Laurie Anne Pearlman’s chapter on building self-capacities, Wendy Lichtenthal and Bill Breitbart’s nice piece on the Who am I? method, Gail Noppe-Brandon’s incisive illustration of dramaturgical listening, and many others.

But the majority of chapters were included precisely because they stemmed from other, even if sometimes related, sources of inspiration–in the expressive arts, body work, play therapy, group process models, traditional healing practices, attachment theory, behavior therapy, family work, spirituality and ritual. Just as loss is universal across the lifespan and across cultures, so too grief therapy needs to draw intelligently on fonts of creativity and compassion originating in many disciplines and traditions.

Q. What is the role of complementary therapies – such as meditation, relaxation and yoga – in helping bereaved people find meaning and/or reengage with life after loss?

A. As contemporary research demonstrates, grief is a multidimensional experience, one that profoundly perturbs our emotional lives, our ability to find sense and orientation in the landscape of a changed world, and even our bodily needs and rhythms. At a deep level, time-honored practices of mindfulness, meditation, relaxation, imagery work and yoga help restore a sense of equilibrium compromised by loss, ultimately yielding greater clarity and compassion for self and others during a turbulent passage.

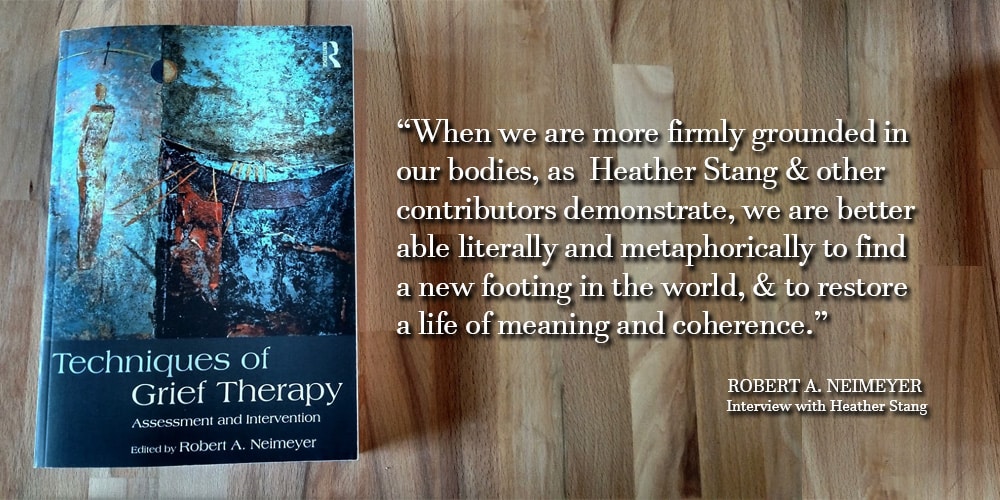

When we are more firmly grounded in our bodies, as Heather Stang and other contributors demonstrate, we are better able literally and metaphorically to find a new footing in the world, and to restore a life of meaning and coherence.

Q. In your experience and based on your extensive research, what are some of the common needs of bereaved people?

A. My colleagues and I have indeed done a good deal of research, but so have many other contributors to the book, such as Kathy Shear on Complicated Grief Treatment, Camille Wortman on patterns of resilience in widowhood, Emmanuelle Zech on the Dual Process Model, Anthony Papa on behavioral activation and many others.

What emerges from all of this burgeoning research is hard to summarize in a sentence or two, but in general it points to the rather different paths through grief that the bereaved experience, some of whom cope remarkably well by drawing on their own resources and those of their families and communities, while others struggle greatly, and also benefit greatly from specialized interventions for the unique ways they become stuck in the process of adapting to a loved one’s death.

By offering a very well stocked toolbox for professionals supporting them, TGT2 should go a long way toward meeting the needs represented by many of the bereaved, whether for general support with a difficult transition or for very specific professional interventions addressing unique complications.

Q. Who is most likely to benefit from reading this book? What do you hope they will gain from reading it?

A. That’s an easy one! Practicing therapists of many professions (social work, psychology, family therapy, pastoral care, counseling, nursing and occupational therapy) who join with clients and patients in a moment of great pain but also possibility, and who accompany them in their quest to find meaning in the loss and in their changed lives in its wake.

Like its predecessor, TGT2 offers a great trove of resources to creative clinicians, whether they are seeking to ground their practice in the emerging evidence base for grief therapy or are looking to expand their imagination of what can be accomplished at this existential juncture. There is a world of wisdom to inform how we can help, and TGT2 was compiled to grant greater access to it.

Techniques of Grief Therapy: Assessment and Intervention is available on Amazon.com and through most booksellers.