Lessons from Yoga That You Don’t Have to Be a Yogi to Practice

When we are in pain, what we need more than anything else is compassion and kindness. Sadly, that’s not always what we get.

As a grief counselor and a yoga therapist, I’ve come to realize that the core of what I teach clients, in private sessions, in a yoga class, or in retreat settings, always comes back to self-compassion and self-care. In yoga, this aligns with the teaching of ahimsa. My Mindfulness & Grief podcast Episode #3 with Heather was about this very thing: Ahimsa.

The first and most basic teaching of the Eight Limbs of Yoga, Ahimsa is usually translated as non-violence or non-harm, but the easiest way to refrain from doing harm, and potentially doing good, is to actively practice kindness and compassion.

For grieving people, practicing self-compassion and self-care is often very difficult. All humans share the inclination to want to relieve discomfort when we find ourselves in it. In grief and trauma, we find ourselves in many moments where, try as we might, we cannot alleviate our own discomfort and pain. This can cause us to feel worse about ourselves.

As members of a culture that is averse to any experience that’s not “positive” or happy, we judge ourselves for “still being sad” or “not doing better.” We absorb and hold ourselves to the same unrealistic expectations projected from the world around us. Society expects the bereaved to start getting back to “normal” about three months post-loss, sometimes sooner. And “normal” usually means your pre-loss functioning and self. This is often impossible. We are changed after a traumatic loss and there is no going back to who we were. There is also truly no timeline on grief. It takes as long as it takes. What we need during the process are kindness and compassion. From others as well as from ourselves.

Friends, acquaintances, family, doctors, co-workers, bosses, clergy, and sometimes strangers—all part of our shared grief aversive and death-denying culture—often give explicit and implicit messages to the bereaved to do something; take a pill, go see somebody, get past it, rise above it, let it go, find the gift, or the silver lining. While these messages may be given out of love and concern, they often cause more pain. And just for the record, there isn’t always a silver lining.

If these others looked closely at their own motivation, they would see that too often, what they want is to ease the discomfort of their own feelings, thoughts, and fears related to grief, and of death. They very rarely know this. They also genuinely want to relieve the distress of seeing someone they care for in so much pain. What they also don’t realize is that there are things that cannot be fixed and grief is one of them. They also do not realize that alongside the desire to help the grieving, is also the desire to help themselves feel better. What they need for themselves are kindness and compassion.

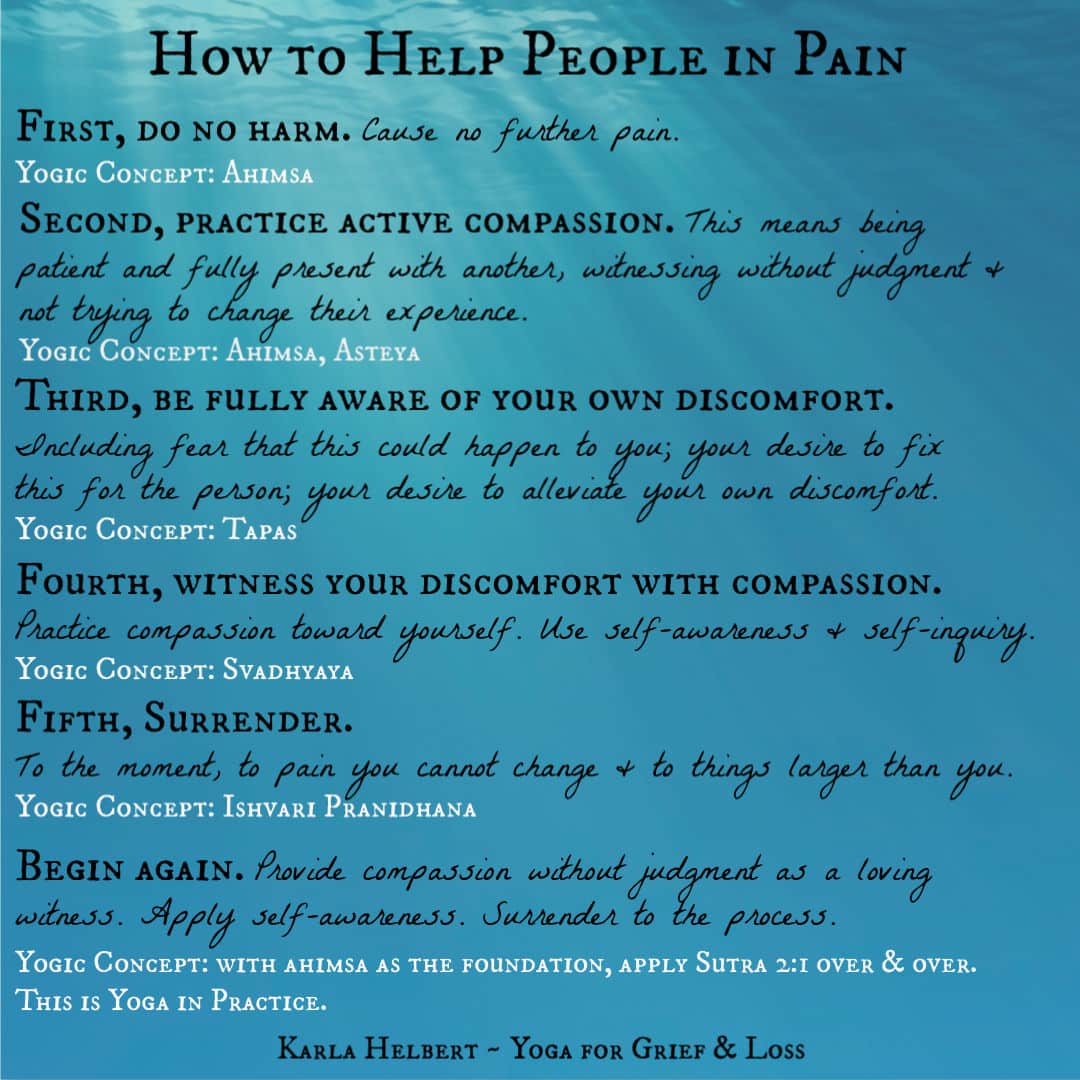

The teachings of yoga provide an excellent guide for practicing kindness to ourselves and to others who are in pain and grief. When practiced, this model works in absolutely all situations. Like mindfulness, the model is simple, but not easy. There are five steps to this practice.

Step One: First, Do No Harm.

In yoga, this is the basic concept of Ahimsa. Non-violence, non-harm. Not causing pain. Sadly, humans beings are often violent. Our capacity for violence of all kinds is our worst quality and greatest failing. Acknowledging our own capacity for violence—toward ourselves and others—is the beginning of change for all. Awareness is the beginning of all change. For bereaved people, beating ourselves up for feeling sad, for continuing to have griefy days and tearful moments, is not helpful. Putting things in perspective and treating yourself with love and compassion can be such a gift. You have been hurt enough, don’t add to your pain.

For non-bereaved people, pause before speaking or acting and ask yourself if what you are about to do or say might cause any amount of increased pain. If you are unsure, then do not do or say that thing. Saying, “I am so sorry,” will generally not cause any further harm. Also, “There are no words, but I am willing to be here with you” is a good choice. Any platitude, anything that begins with “At least…” any comparison to anybody else’s losses are likely to cause pain. Any attempt at reassurance that “everything happens for a reason,” or “perhaps it was better this way,” or reminders that the person is “in a better place,” are not helpful and often cause more pain. Do not say those things. Just don’t say them. Mahatma Ghandi said, “Speak only if it will improve upon the silence.” Simply being a witness is the least harmful thing you can do. Do not cause more pain. This leads to the next step.

Step Two: Practice Active Compassion

This means being patient, fully present, witnessing without judgment, and with as much compassion as possible. The word compassion comes from the Latin roots pati, passio, and passionem, all meaning “to suffer.” The word “patient” has the same root. The prefix “com” means “with.” Understand this clearly: Compassion means to “suffer with.”

For bereaved people, this means having patience with yourself, and as little judgment toward yourself and your own suffering as possible. I often ask clients and students to, in this moment, place your hand on your heart, close your eyes, connect with your breath and heartbeat, and ask, “What is the most compassionate thing I can do for myself right now?” And then do that thing. Sometimes it may be simply breathing through this moment. Giving yourself a little hug. Allowing yourself space and time to feel what you feel.

For others supporting someone in pain, active compassion means being fully present, patient with the other person’s pain, and not trying to change their experience. This can be very difficult and uncomfortable.

Step Three: Be Fully Aware of Your Own Discomfort

For bereaved people, this means being present to your pain as often as possible. This may seem like a ridiculous thing to say, as we often feel we can’t get away from the pain and we really want to get away from the pain. But cultivating a practice of being mindful of what we are enduring, rather than mindless, can help us recognize grief and its many aspects. When we seek to avoid or escape our pain, we become less equipped to manage it when it arises or takes us by surprise. Sometimes, breathing through it one breath at a time is truly the only thing you can do. And that is no small thing.

For non-bereaved others, your discomfort around someone else’s pain may include feelings of helplessness, fear that this could happen to you or to someone dear to you. Your discomfort may include wanting to get rid of the discomfort as soon as possible. This is a crucial thing to recognize if you want to truly help another. When we seek to alleviate our own discomfort around someone else’s pain, it almost always causes additional pain for the person who is hurting. Platitudes, filling the space because silence is difficult, the need to “fix;’ all these things are not truly helpful. See Steps One and Two.

Step Four: Witness Your Discomfort with Compassion

This step also requires practicing self-awareness and self-inquiry. For the bereaved, this means first, having compassion for yourself. Using self-awareness, acknowledge your process in grief, noticing what you are telling yourself in your pain, whether you are being kind or whether you are causing more harm to yourself with your inner dialogue. Often the things we say to ourselves in grief and pain are not only unkind, they are also untrue. Using self-awareness can help us avoid telling ourselves untrue and unkind things. Practicing this step helps us to be more compassionate and realistic in our own expectations of ourselves.

For others, this means something very similar as it means to the bereaved. Notice your inner dialogue. Where is your discomfort coming from? Is it fear based? Is it helplessness? Guilt or shame-based? Are you judging the hurting person’s feelings or how they are responding to this pain? Ask yourself how you might feel in their situation. If you find yourself saying something like, “I can’t imagine…” please check that thought for a moment and recognize that you can imagine. You may not be able to really truly know for sure what their experience is like, but you can imagine. Notice that if you try to imagine in detail what it might be like to experience that pain, those circumstances, how uncomfortable this makes you. Practice compassion toward yourself and breath.

A note here: When you feel the urge to say “I can’t imagine…” to a person in grief or pain, know that statement may cause more harm. To alter it a tiny bit saying “I can only imagine…” changes the entire tone of the statement. It means that you are trying to imagine what it must be like, which creates connection and empathy rather than isolation. This may seem like a small distinction, but it is important and makes a difference.

The human imagination is unlimited. Think of all the amazing and terrifying things humans have imagined. When we say we can’t imagine what someone in deep pain is going through, what we’re really doing is saying we don’t want to imagine it because it is too scary and too awful. When someone is sharing their painful story, do imagine, see what happens inside. Notice what reactions you experience physically, emotionally. When you imagine someone else’s tragedy happening to you, what you experience is discomfort, sadness, pain, fear. This brings you closer to true compassion. Suffering with.

Step Five: Surrender

For bereaved and non-bereaved people this is very difficult because we don’t want to surrender to grief or discomfort. We want this not to have happened. When every cell in your being cries out against something, surrendering is no easy task.

For non-bereaved surrendering to your discomfort and practicing self-awareness is also difficult. Surrendering to the knowledge that this terrible thing has happened and you can do nothing to fix it. All of this requires tolerating distress. This takes practice. It’s hard.

Surrender is not about giving up. It is a way of moving toward and leaning in, as much as we possibly can, to the pain, the challenges, the doubt, the anxiety, the fear, the hurt, the changing tides of emotions and of uncertainty. The idea of surrender can bring with it opposing feelings of relief and opposition in equal measure. To surrender is to release control. This is uncomfortable because we believe that if we remain in control, we can stave off the pain, relieve anxiety, and ultimately stop bad things from happening. But this is not true. We can never really stop bad things from happening. We can do our very best to take care of ourselves and others, but ultimately, we must release the notion that we control anything other than ourselves and our own reactions, responses, and behaviors.

Surrender here means, surrendering to the moment; to circumstances and to the pain that you cannot change and to things that are bigger than you.

Step Five: Begin Again at Step One – Do No Harm.

Practice active compassion. Be self-aware and fully present to all that is happening. Surrender to the process. Keep doing those things.

These are five steps; simple but not easy.

Can you pause for a moment before scrolling on and placing your had on your heart, taking a long slow breath, close your eyes and ask yourself, “What is the most compassionate thing I can do for myself right now?” And give yourself permission to do that thing.

For more with Karla, listen to her interview with Heather Stang, “Ahimsa: The Yogic Path to Self-Care During Grief with Karla Helbert.