Almost everyone experiences bereavement and grief at some stage in their lives, yet no one experiences it in the same way. We are all different in the way we respond. In the midst of grief, it is difficult to accept intended words of comfort such as “I know how you feel.” Such words always sound hollow and insincere. Also, there is no “normal” style or duration of bereavement. For some the journey seems to pass in months, for others it can take years.

In truth, it seems that bereavement never ends: “it changes and, in the process, changes your life” (Grieving Mindfully, SM Kumar).

My Journey

When my wife died of cancer 10 months ago, I was surprised how unprepared I was, despite sharing her sad decline over three years following a pessimistic early prognosis. When the end came, I was in a state of shock, on automatic pilot for several weeks, before the shock gave way to a general numbness. Like coming round after a general anesthetic, there was a slow and blurred realization of what had happened . Anne was dead, and after 42 years of a happy partnership, I was on my own and apprehensive about the future and my own mortality.

As the numbness evaporated it was replaced with a fear and anxiety which I had never felt before. It was a struggle to control this fear until I was able to achieve a more relaxed state, albeit now in a mood of sadness and loneliness.

My first response to my newfound situation was to try and find out what was happening to me. What is bereavement? How long would it last? What did I need to do to cope? I soon discovered that because everyone is unique there is no general purpose guide book to bereavement.

However, I continued to search for answers by reading any available books or articles on the various theories of bereavement in the hope that, if I could learn about the theory, I might gain an understanding of the confused thoughts and fears that were going through my head. This was not a morbid interest. I found a kind of solace in my research, especially when coming across academic findings which struck a chord with me and helped to illuminate my position. I stumbled upon some of these findings in retrospect, at other times I read pieces which gave me an insight into what I could expect to encounter on my journey.

Styles of Mourning

During the course of this introspection, there were times when I began to wonder if my interest was becoming an unhealthy obsession. I then found a piece of research which categorized the ‘styles of mourning’ into 3 basic types:

- Intuitive mourners who experience a rich range of emotions and are less able to rationalise the pain of grief and are more likely to appear overwhelmed by it.

- Dissonant mourners who encounter a conflict in the way they experience their grief internally and the way they express it externally.

- Instrumental mourners who experience and speak of their grief intellectually and physically. They may speak of their grief in an intellectual way, thus appearing as cold and uncaring.

Assuming the validity of this research, I found it reassuring to know that, whilst my “instrumental style” of mourning might not be typical, it was not unheard of or abnormal.

The Theories of Grief

There are several theories about the nature and process of grief:

- the five stages of grief (Kubler-Ross)

- the tasks of grief (W Worden)

- the dual process of grief (Stroebe and Schut)

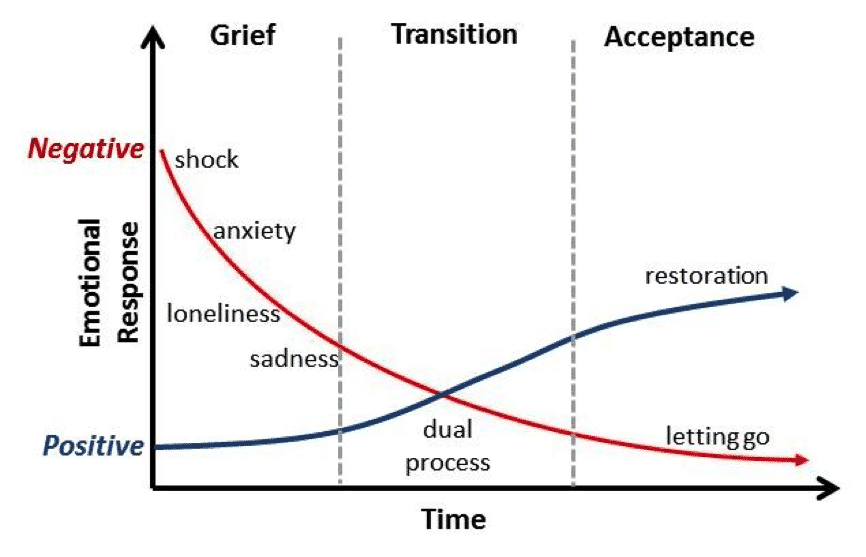

The earlier theories speak of the five stages of grief, ranging from Denial through Anger, Bargaining and Depression to Acceptance. Other, more recent theories refer to the four tasks of grief: the reality of the loss; the pain of grief; adjustment to loss and embarking on a new life. Another examines grief as a dual process, oscillating between loss-orientated responses and restoration-orientated responses.

Having read about them, whilst none provided a close fit to my own experience, I found that I could relate to various aspects of the different approaches and was able to describe my story so far in terms of an emotional balance sheet.

A Bereavement Balance Sheet

From an earlier encounter with cognitive behavioral therapy as a response to depression, I had become used to thinking about my life in terms of positive and negative emotions—a series of “good days” and “bad days.” In a normal span, apart from the usual mishaps (“bad days”), the positives generally outweigh the negatives. When bereavement strikes, this is clearly not a “usual mishap,” and the situation is inverted, with all positive emotions extinguished, and the world is suddenly a dark and negative place.

Extending this analogy, it was as if Anne and I had experienced a healthy joint emotional bank account throughout our married life, always in credit. With the cancer diagnosis, over a period of three years, this balance slowly diminished but remained in credit. On Anne’s death, I became emotionally bankrupt overnight and stayed in that state for several months; only in recent times, has my emotional bank account become healthier and has seen fluctuating periods in credit.

This perception is compatible with my understanding of the dual process model, with the counterplay of “pluses and minuses,” while, at the same time, there is a discernible sequence of “stages” or “tasks.”

I have tried to illustrate this balance sheet approach in diagrammatic form.

In reality, the lines on the graph should not be smooth curves, but should appear rather like a seismograph, with frequent ups and downs along their length. In the transition phase, there is a counterplay between the negative and positive emotions, with the positives gradually prevailing into the restoration or acceptance phase. In bank balance terms, the positive emotions are “credits” and the negative ones are “debits.”

Acceptance: The Goal

‘In the acceptance phase, you learn to accept the loss and integrate it into your life. It’s not so much that you are fine with the loss. Instead, your mind, body and emotions are finally able to accept what has occurred, and you see it as something you can assimilate into your everyday life, thoughts and feelings’.

Julie Chen Accepting and Embracing Grief

Acceptance, as described in this way, must surely be the goal of all who have been bereaved, especially for those whose journey has been long and tortuous, for grief and acceptance can be seen as opposite sides of the same coin: as grief decreases, acceptance increases.

Acceptance is to be at peace with what has happened and to be able to look forward to the future without pain or sadness.

As I write this, I feel that I have not yet reached this goal, but I am optimistic that it is attainable, although there is always the fear of unexpected ‘triggers’ which can cause a relapse.

How to Get There

I have found nothing in the literature which gives guidance on how to reach this goal quickly, for there are no shortcuts or ways of ‘fast forwarding’ the experience.

However, in mindfulness I have found measures which can ease the pain and help to avoid wasteful energy and stress along the way. The popular Serenity Prayer encapsulates this philosophy:

…grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

the courage to change the things I can.

and the wisdom to know the difference.

In addition to help in relieving stress and ‘grounding’ oneself, there are also exercises which help in confronting loss in a gentle and compassionate way. This is perhaps the most fundamental mindfulness practice in learning to live with one’s loss rather than to stay in a state of denial or avoidance.

A Mindful Future

Bereavement exemplifies the truism that you do not know what the future holds and that life is uncertain and unpredictable. For my part, I am very grateful that, through the support group and the guidance of the clinical psychologist at Maggie’s cancer charity, I discovered, at an early stage, ways of adopting a cognitive or mindful approach to my bereavement. Without that intervention I think I would have floundered and, perhaps, got stuck at some stage of the journey.

Whilst I have not fully embraced or tried all the practices that mindfulness contains, I have learned enough to realize its potential benefits in being able to observe my thoughts and emotions more clearly and objectively. It has become a kind of mental physiotherapy as well as a form of insurance for the future.

Of the books which I have read, there is one which resonated most closely to this mindful approach: ‘Grieving Mindfully’ by SM Kumar. It contains many profound references, some of which I don’t fully understand, but I think I grasp the gist and message of hope in its conclusion:

Grief does not end; it changes and, in the process, changes your life. The sharp twists and turns of the spiral staircase gradually soften to reveal the treasure of grief – your choice to live your life differently, aware of how precious and precarious life is for all of us. This transformation of grief carries a potent message: that you can use life’s challenges to grow, to become a better person.